Roman, Renaldo, and the DA’s Racism Reckoning

Lindiwe Mazibuko, Patricia de Lille, Herman Mashaba, Mmusi Maimane, Bongani Baloyi, Patricia Kopane, Makashule Gana, Mbali Ntuli, Phumzile van Damme, and Khume Ramulifho—names once proudly emblazoned on boundless blue posters across the country, now reduced to mere whispers, swept under the rug by the Democratic Alliance (DA) like inconvenient truths.

But these names refuse to fade, reemerging yet again in the face of controversy, exposing the festering wound at the heart of a party that claims to champion non-racialism but seems to continuously be drowning in racial discord. To DA supporters, the issue may seem trivial—just another example of staff turnover that plagues every political party. But is it? The deeper question remains: how can a party preach non-racialism while harbouring individuals who openly peddle racist rhetoric?

Enter Renaldo Gouws and Roman Cabanac—two names now infamous within the DA. Gouws, a sitting member of parliament, was caught on video spewing racial slurs, including the K-word and N-word. His defence? “I was young and naive,” he claimed. But at 25, can one still cling to such an excuse? Gouws, who has yet to do a sit-down media interview or take any steps towards accountability, was recently approached by political analyst Jamie Mighti and stated, “I have absolutely nothing to say because everything is there.” He then continues to list a string of Twitter apologies he issued but fails to mention the proactive steps he has taken to correct his racist mindset.

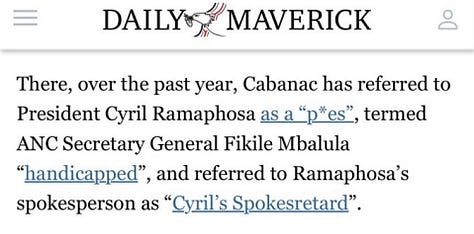

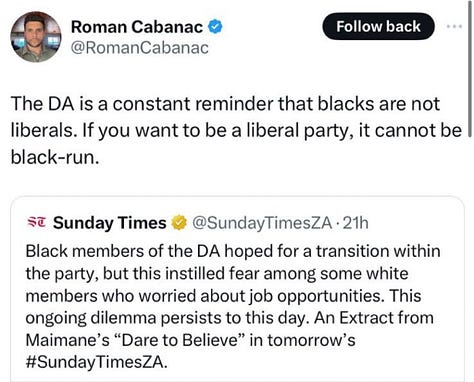

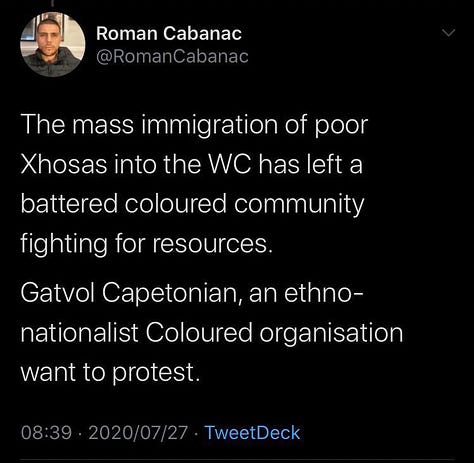

Then there is Roman Cabanac, recently appointed Chief of Staff to John Steenhuisen, leader of the DA. Cabanac, a vocal Trump supporter, has been embroiled in both racial and homophobic controversies. From his unapologetic admiration for apartheid-era South Africa—claiming life was “better pre-1993"—to stating that he would like Freddie Mercury’s music but “he is gay,” highlighting his blatant disregard for the deeply painful history of our country—a country in whose government he now serves.

Steenhuisen’s defence of Cabanac was not one of moral clarity. Instead, he focused on qualifications, praising Cabanac’s LLB degree and legal acumen, as if a piece of paper could absolve the man of his past. But qualifications alone cannot cleanse the stain of racism, nor can they excuse the DA’s broader problem with cadre deployment and nepotism. Cabanac, who now earns R1.4 million annually as one of the highest-paid civil servants, is unqualified for his role within the Department of Agriculture and yet occupies a position of power where his influence can shape policy. The DA’s leadership has repeatedly downplayed these controversies as isolated incidents. But these incidents are no longer isolated—they are part of a growing pattern.

There are those within the DA who argue the party should not "pander to the left," as though confronting racism is a mere political calculation. But this is not about left or right; this is about principle. South Africa’s history is too raw, its wounds too deep, for any political party to turn a blind eye to racism in its ranks. The DA’s refusal to take a firm stand against racism, both within its leadership and its policies, is not just a failure of ideology—it’s a failure of humanity.

The real question that lingers is whether the DA believes in the very values it professes—freedom, fairness, opportunity, and diversity—or if these words have simply become hollow slogans. The continued employment of men like Gouws and Cabanac suggests the latter. As long as the DA continues to turn a blind eye to its internal rot, it will continue to lose credibility amongst its 3 million South African voters. Its claims of non-racialism will remain hollow, and its moral compass, broken.